Colorado University Athletics

CU Athletic Hall of Famer Billy Lewis Passes Away

June 28, 2011 | Men's Basketball

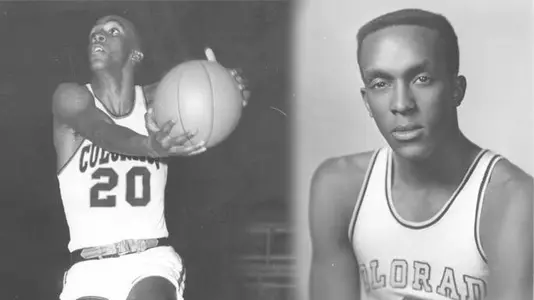

BOULDER - University of Colorado Athletic Hall of Fame member Billy Lewis, the school's first African-American varsity basketball player, has passed away at the age of 72. He died in his Atlanta home on June 14.

Lewis was inducted in CU's Athletic Hall of Fame in October 2008, and gave a very emotional speech before 500 people, which included about a dozen of his relatives that attended from as far away as Atlanta, Baltimore and even Egypt.

Just a few weeks ahead of America electing its first black president, he talked about how far the country had come from the days where he was a student-athlete and often forced to eat and sleep away from his teammates on road trips because some hotels would not allow blacks on their premises. Some excerpts of his acceptance speech, which onlookers easily could see him bursting with pride:

"In order to receive a full athletic scholarship at CU, or any other Division I school, one has to have above average skills and maintain those skills. They have to be able to compete before thousands of people and know that the pressure of the butterflies that all of us have experienced are character building. Those are the kinds of things that I experienced. My grandmother told me to never let anyone break my spirit. That and the chance to attend a multi-cultural school like (Denver's) Manual High School enabled me to attend a school like CU. It's a blessing for me to be successful and because of what I learned and what I was exposed to at CU, I was never afraid of anything.

"I hope in some small way I have contributed to the success of the university, as it has benefitted me in a myriad of ways."

Lewis graduated from Manual High in the spring of 1956, and enrolled at CU that September; at that time, freshmen were ineligible to play and he thus made his debut in the 1957-58 season. As with his football counterparts who were a year ahead of him, Frank Clarke and John Wooten, though treated well in Boulder, he often had to endure harsh racism on the road in pre-Civil Rights America and thus helped blaze the trail for all those who would follow him to CU.

His best season was his junior year, when he averaged 5.9 points per game with a career-high 21 against Nebraska. The 6-3 forward played in 67 career games, scoring 244 points and grabbing 197 rebounds in lettering three times. In 1959, after the basketball season was complete, he decided to come back out for track in his specialty, the high jump; he cleared 6-6-+ and finished second in the CU Invitational (to Wyoming's Jerry Lane, who jumped an inch higher) which topped his previous personal best of 6-2 as a senior in high school, where he was coached by CU great and Hall of Fame member Gil Cruter, who himself was one CU's first black track athletes in the early 1930s.

Just as important if not more so were his contributions as a student leader, becoming the first African-American elected by the student body as commissioner of the ASUC (Associated Students of the University of Colorado); he led a delegation of students and testified on the resolutions against discrimination in housing and employment practices and headed the SFHD, Students For Human Dignity, two of many causes he championed that helped change CU in a positive way forever.

Upon his graduation from CU in 1960, he clerked for a Denver judge, and after marrying fellow CU grad JoKatherine Holliman (the first African American woman on CU's homecoming court), they relocated to Washington D.C. where he would work for Colorado senator Peter Dominic in 1963 and 1964 while earning his Juris Doctor of Law degree from Howard University. In '64, he was recruited by IBM and took a position as the first African-American corporate attorney at the company's headquarters in Armonk, N.Y., and returned to Colorado two years later (1966) to be the junior counsel for IBM in its Niwot offices.

After nearly making a successful bid to become a state representative in 1968 (he lost to Tom Bastien by just 100 votes), he opened a private law practice in Denver with partner Morris Cole, one of if not the first black law firms in Colorado. He would go on to serve as general counsel at Howard University and then vice president of government relations for the Putney Hospital Group in Albany, Ga.

Born in Kansas City, Mo., in 1938, Lewis is survived by both his first wife and his second-wife, Pauline Dickinson; he was the father of four, Cynthia, Hank, Michael and the late Leslye Mundy, and is survived by six grandchildren, Taylor Cheek-Mundy, Alva Robertson, Wesley and James Lewis, Nina and Hughes Mundy, two sisters, Mary Ellen Russell and Carol Ann Sanderson; nephews Shawn Sanderson and Todd Russell; niece Heather Russell; stepchildren, Joseph, Craig and Kyle Shields and their five children.

Many of Lewis' colleagues in the professional world along with several long-time friends from Manual and former Buffaloes attended the memorial service held June 27 at Zion Baptist Church in Denver.